An animal like Broomistega would usually avoid being near others, but this one was different. Its injuries, which included a sequence of broken, partially-healed ribs, would have made it difficult for the amphibian to move and breathe. The injured Broomistega probably sought refuge in the burrow to escape the hot sun of the dry season, especially if it was unable to move and breathe adequately.

If the Thrinaxodon remained undisturbed during its long naps, as Fernandez et al. believe it did, then the amphibian might have been able to sleep in the cool without fear of getting kicked out. In the Triassic, animals slept and died together, becoming fossilized together.

Triassic cuddle

In the 1975 year Oliviershoek Pass in South Africa, paleontologist James Kitching discovered the fossil of a tiny, four-legged mammal that had lived 250 million years ago. The deceased creature was identified by the shape and composition of the surrounding rock as having died in a cave, and when Kitching split open the rock, it was discovered that there were more bones inside.

Johannesburg’s Evolutionary Studies Institute of the University of Witwatersrand received the fossil after Kitching discovered it. The little beast was a very rare Triassic mate.

Triassic cuddle Wattpad

The specimen of the extinct mammal Thrinaxodon that Kitching spotted was buried in a sand dune. A number of Thrinaxodon skeletons have been discovered curled up inside their dens, suggesting that Thrinaxodon sought refuge from the harsh dry season heat by sleeping there. Whether or not Thrinaxodon built their own dens is unknown, but their fossilized remains appear to indicate that they slept there.

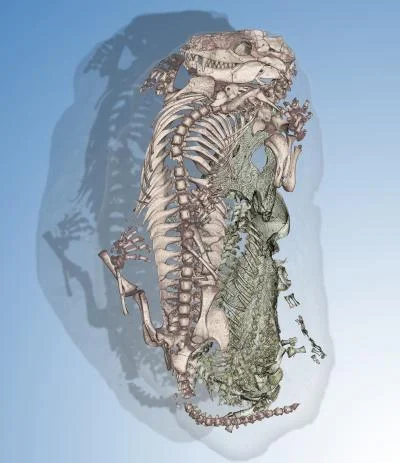

A salamander-like amphibian named Broomistega is also found in the triassic cuddle tomb. It is lying on its belly above Thrinaxodon, a protomammal. Until paleontologists from the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa and colleagues had the contents of the burrow imaged at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility in Grenoble, France, no one knew about the bonus fossil. Its incredible position was depicted in a recent digital representation.

Fernandez and colleagues narrowed down the list of possibilities for how this Triassic mash-up came together based on the fossil.

Triassic cuddle Wikipedia

It is unlikely that the Thrinaxodon created the hollow in the Broomistega burrow, so it is believed that the protomammal was the den’s primary resident. Even if both animals were entombed by a flood of water and mud that rushed into the burrow, it would be quite a coincidence if the sloshing mud happened to carry an intact amphibian right into the den.

A burial of Broomistega in a Thrinaxodon burrow is unlikely to have been accidental. The amphibian either dragged Broomistega in or hauled itself down for an accidental burial. It seems more likely that Broomistega haphzed to Thrinaxodon instead of being dragged in. Even though the Broomistega bones show two possible tooth puncture marks, the Thrinaxodon’s dental measurements and spacing did not match. The amphibian was sound asleep in a temporary torpor when Broomistega wandered into the burrow and was buried in the muck.

Final Line

Even among modern animals, close cohabitation is uncommon, but the Broomistega might have had good reasons to seek shelter. For example, the amphibian suffered from a series of broken, partially-healed ribs, which presumably impaired its ability to move and breathe. Because it would quickly die if stranded in dry season sun as a result, the injured Broomistega may have sought refuge in the burrow.

As long as the Thrinaxodon lay undisturbed in a multi-day slumber, as Fernandez and colleagues suggest, the Broomistega might have been able to rest in the cool without being driven out by the burrow-owner’s snapping jaws. While dozing, dying, and becoming fossilized together, triassic cuddle neighbors cozied up together in the dark and the cool.